讲座 Talk · Wolfram Knauer | 现代德国爵士 German Jazz Today

本文为第四届OCT-LOFT国际爵士音乐节讲座讲稿

未经允许,不得转载,如需转载,请联系 midori@b10live.cn

讲座简介 Introduction of the talk

爵士乐是来源于非裔美国人的音乐,但它却征服了整个世界。世界各地的音乐家们不仅以美国爵士乐为模范,并且不断给予它不同音乐背景的影响。在德国,爵士乐已经成为创新音乐表达的一个重要形式,并得到一群忠实的听众、形形色色的俱乐部、音乐节等业界的支持,所需资金则通过广播、市政公用和区办公室及政府来筹备。

达姆施塔特市德国爵士研究所(Jazzinstitut Darmstadt, Germany)于1990年建立,并已成为欧洲最大的爵士乐公共档案文件和信息储存中心,可提供世界各地的爵士乐的主要信息资源。Wolfram Knauer在达姆施塔特市德国爵士研究所建立之际便担任所长,他将在此次讲座中谈到现代德国爵士乐的多样性和运行这样一个组织的重任,并向观众展示该组织是如何联结音乐场景和业界、演出、观众和文化政治的。讲座内容也会简单涉及到爵士乐和即兴音乐作为我们全球化世界背景下的创造性动力的重要性。

Jazz was born as an African-American music, but it has since conquered the world, asking musicians from around the globe to both follow the model of the American original and add influences from their own musical backgrounds. In Germany, jazz has become an important form of creative musical expression, supported by a devoted audience, by a diverse club and festival scene and by funding through radio, public municipal and regional offices as well as the national government.

The Jazzinstitut Darmstadt has been founded in 1990 by the city of Darmstadt, and has since become the largest public jazz archive and information center in Europe and one of the major sources for information about jazz worldwide. Wolfram Knauer has been the Jazzinstitut's director since its inception and will talk both about the diversity of current German jazz and about the tasks of an organization connecting the music scene, its audience, and cultural politics. He will also touch upon the importance of jazz and improvised music as a creative force in our globalized world.

讲者简介 Introduction of the Speaker

Wolfram Knauer是一名音乐学家,自达姆施塔特市德国爵士研究所1990年创办以来一直担任所长。他写作并编辑了超过14本爵士乐相关的书籍,同时也是学术期刊《Jazz Perspectives》的编辑董事会成员之一。他在几个学校和大学任教,并在2008年的春天被任命为纽约哥伦比亚大学的爵士乐研究中心路易斯·阿姆斯特朗(Louis Armstrong)基金会的客座教授,成为了该中心第一位非美国籍的客座教授。

达姆施塔特市德国爵士研究所为学术性需求和实践性需求搭建起桥梁,创立了地区性的和多元文化的活动,进行具有跨国学术性的演说,这些都是为了支持音乐和那些让音乐充满生机并持续发展下去的人。达姆施塔特市德国爵士研究所凭着它对与爵士乐相关的可靠的调查探究,在爵士乐界中赢得了声誉。

Wolfram Knauer is a musicologist and the director of the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt since its inception in 1990. He has written and edited more than 14 books on jazz and serves on the board of editors for the scholarly journal Jazz Perspectives. He has taught at several schools and universities and was appointed the first non-American Louis Armstrong Professor of Jazz Studies at the Center for Jazz Studies, Columbia University, New York, for spring 2008.

现代德国爵士 German Jazz Today

讲者 Speaker:Wolfram Knauer / 现场翻译 Interpreter:程璐璐 Cheng Lulu / 时间 Date:2014.10.12

明年,达姆施塔特爵士研究所将会迎来建所25周年的庆典。研究所成立于1990年,但达姆施塔特市对音乐积极扶持的历史可以上溯到1946年。在我的讲座中,我会向你们介绍一些我们在研究所的工作,时下德国的音乐,以及我们所有人——音乐家、推广者、评论家,以及乐迷、爵士乐死忠等——如何在志愿者的支持下努力确立一种爵士乐的环境,而这已经成为德国文化一个主要的艺术发声。

Next year, the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt will celebrate its 25th anniversary. It was founded in 1990, but the history of active music support in the city of Darmstadt goes back until 1946. In my presentation I will tell you a little bit about what we do at the Jazzinstitut, but also about the music which can be heard in Germany at the moment and how we all, musicians, promoters, critics, as well as fans and jazz enthusiasts try to secure a scene which is based on many volunteers and yet has become a major artistic voice for German culture.

让我们先听一段音乐,这是德国贝斯手Sebastian Gramss的五重奏2014年4月的录音,低音单簧管Rudi Mahall,吉他Frank Wingold。Gramss来自爵士乐氛围非常活跃的德国科隆,在他名为“Underkarl”的项目里,他把对爵士史的深刻理解与近当代的声音表现结合起来。在真正的合奏开始前,乐曲是以Wingold刮擦一张他们自己的黑胶唱片起头的。我想用这首曲子开始的原因是,之后我们将叙述爵士史的发展,而我希望你们了解爵士乐的目的地在哪里,它永远是:今天,又或者说,明天。

Let us start with some music, recorded in April 2014 by the quintet of the German bassist Sebastian Gramss with Rudi Mahall on bass clarinet and Frank Wingold on guitar. Gramss is a musician of the vibrant Cologne jazz scene, and in his project called “Underkarl” he combines contemporary sounds and approaches with a deep appreciation for jazz history. The track starts with Wingold scratching a vinyl record of the band before the real ensemble takes over. I want to start with this because after it we will move through jazz history and I want to make sure you know about the destination, which in jazz always is: today, or rather: tomorrow.

♬ 点击播放视频 Video:Underkarl《Sdölk》

我就从对德国爵士史的简短回顾开始吧。爵士乐在上个世纪20年代传入德国,当时被大家当作一种新的舞会音乐。乐手们在柏林、慕尼黑、汉堡等一些大城市中受欢迎的俱乐部、咖啡馆或酒店里演出,尽管他们几乎没听过“真货”,就是说他们很少能接触到真正的美国爵士乐。他们不得不依靠他们对爵士的想象,主要通过从乐谱、乐评以及与其它音乐家的争论中获得的一种认知,来靠近爵士乐的观念。很多人把特定的乐器——比如萨克斯、班卓琴、爵士鼓,或者把以特定的方式来演奏古典乐器,或者把特定的节奏表现,又或是把很多乐器合奏时产生的一种狂乱的声音,来作为爵士的象征。乐手们也许听过即兴这个概念,但是很少有人真正知道如何即兴。请注意,这是唱片诞生之前的时代,你若非在音乐现场听过,就是从未听过。不过20年代中期,第一个美国爵士乐团来欧洲巡演,德国人突然就能听到真正的爵士乐了。1928年,第一个爵士乐课程在法兰克福音乐学院开办。它旨在从不同方面教授舞会乐手“当代爵士乐演奏”。尽管一些当代古典作曲家,如Igor Stravinsky、Ernst Krenek、Paul Hindemith等都曾经在自己的作曲中运用到爵士元素,但是爵士乐在当时仍然不被认为是一种和欧洲古典音乐水平相当的艺术形式。

Let me start with a short look back into German jazz history. Jazz came to Germany in the early 1920s and was celebrated as a fresh dance music. The musicians playing the music in the popular clubs, cafés or hotels in Berlin, Munich, Hamburg or other big cities, had rarely heard the “real thing”, though, which means they had rarely been in contact with authentic American jazz. They had to rely on what they thought jazz was, a perception mostly informed by sheet music, by written commentaries, and by other musicians struggling to come close to the idea of jazz. For many, jazz was symbolized by specific instruments – the saxophone, the banjo, the drum set –, by specific ways of treating classical instruments, by specific rhythmic interpretations and by a wild sound achieved by many instruments playing together collectively. Musicians may have heard of the concept of improvisation but few knew how to really improvise. Remember that this is before the record era; you either had to hear the music live or you did not hear it at all. Then, by the mid-1920s, the first American jazz ensembles toured Europe, and suddenly it was possible to hear the real thing. In 1928 the first jazz class was established at the Frankfurt conservatory. Its aim was to teach dance musicians the different aspects of a “modern jazz interpretation”. Although some contemporary classical composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Ernst Krenek, Paul Hindemith and others had used jazz elements in their compositions, jazz was not yet considered an art form on a similar level as European classical music.

上世纪30年代,德国对爵士乐的吸收陷入停滞。国内的政治风气不支持任何一种不“德国”的艺术,它还反对任何掺入个人主义的艺术形式。爵士乐被纳粹正式禁止,乐手们被勒令不许演奏爵士曲,爵士乐迷则被宪兵迫害,有时甚至会被关入集中营。在1933至1945年间,爵士活动在我们的国家基本上被全面禁止。然而,你很难封禁一种音乐,尤其是在那个时代如此流行的爵士乐。因此在爵士乐被官方禁止期间,它依旧在乐迷和乐手中的地下圈子里残活着,即便在当时那样的环境下,乐手们还在尽其所能地演出。

In the 1930s the jazz reception in Germany came to a halt. The political climate in the country did not support any kind of art which was not considered German; it also opposed any art that was engaging in individualism. Jazz was officially banned by the Nazis; musicians were not allowed to play jazz titles, the fans of the music were persecuted by the state police, sometimes even interned in concentration camps. Between 1933 and 1945, jazz life basically came to a halt in our country. However, it is hard to ban a music, especially if it is as popular as jazz was at that time. And thus, while American jazz was officially banned, it survived in underground circles, among fans and musicians who continued to play it as good as they could under the circumstances.

二战结束之后,爵士乐迎来了爆炸般的蓬勃发展,它变得极受欢迎。年轻的乐手和乐迷开始演奏爵士,许多美军驻扎的军中俱乐部雇佣德国乐手为美国士兵演奏取乐。

When World War II was over, the jazz world literally exploded. The music became immensely popular. Young musicians and fans started to play jazz, and many of the military clubs within the American army bases offered German musicians jobs to play for the entertainment of the American soldiers.

上世纪四五十年代见证了年轻的德国爵士是如何继承美国爵士乐的新潮流的——模仿学习它的风格,尝试从听觉上更接近他们的偶像。有些音乐家偏爱从新奥尔良爵士到摇摆乐这种更加传统的风格,有些音乐家则尝试演奏如波普、冷爵士和硬波普这类更加现代的音乐表达。德国爵士在这个阶段的特征是,德国的乐手们纯熟地掌握了既定风格的句法表达,却几乎没有任何乐手能够将其发展为一种属于自己的风格。

The 1940s and 1950s saw a young German jazz scene adopting the new trends in American jazz, learning the idiom, trying to sound like their idols. Some musicians favored the more traditional styles from New Orleans jazz to swing, others tried their hands in more modern idioms like bebop, cool jazz and hard bop. This phase of German jazz reception was characterized by musicians mastering the idiom; however, hardly any musician in Germany, at that time, developed a specific style of his own.

所谓的欧洲爵士乐的“解放”发生在1960年代——请记住我在这里所指的这种大致的发展状况是遍及整个西欧的。当时,年轻的音乐家在遇到他们的美国同行后,意识到原来爵士乐的基本法则是:“哥们,玩你自己的!”这个规则暗示你不仅要了解爵士传统的词汇,还要深入探寻你自己的音乐背景,以发展出一种个性的声音。一些德国的爵士音乐家,如Albert Mangelsdorff或是Alexander von Schlippenbach,正是发展出了一种特别的音乐语言,这种音乐语言既深刻地扎根于他们的美国偶像乐手的音乐,又向内审视他们自己的音乐理解。

The so-called “emancipation” of European jazz – you have to remember that the general development I am describing here, happened all over Western Europe – the so-called “emancipation” of European jazz happened in the 1960s. It happened when young musicians, meeting their American colleagues, realized that the basic rule of jazz was, “Play yourself, man!”, a rule which implied that you had to know the vocabulary of the jazz tradition, but you also had to search deep into your own musical background to develop a personal voice. German jazz musicians such as Albert Mangelsdorff or Alexander von Schlippenbach developed a musical language deeply rooted in the music of their American idols, yet also looking into their own musical socialization.

例如,Mangelsdorff曾在他的曲子中用了一首16世纪的赞美诗《Es sungen drei Engel(三位天使所唱的歌)》。1963年,Mangelsdorff和他的五重奏受德国文化机构歌德学院之邀进行亚洲巡演,他们决定将该桥段替换成各个所到之处的当地民歌。为了体现自己的祖国,他们还在节目单里加入一支古老的德国民谣。现在我们来听一下这首基于泰国当地民歌的《Now Jazz Ramwong》。

Mangelsdorff, for instance, used a chorale from the 16th century for one of his pieces, “Es sungen drei Engel” (Three Angels). This came to pass when Mangelsdorff and his quintet were hired to do an Asian tour for the Goethe-Institut, Germany's cultural institution, in 1963, and they decided to play a folk song from each of the different countries they visited. To show where they came from, they added an old German folk tune to their repertoire. Here is “Now Jazz Ramwong” which is based on a Thai folk song.

另一方面,Alexander von Schlippenbach曾经在科隆音乐学院学习古典作曲,他希望把一些当代古典乐的作曲技法运用在他与他的一些小编制乐团,或者与大编制的环球大乐团(the Globe Unity Orchestra)同台演出的即兴项目里。

Alexander von Schlippenbach, on the other hand, had studied classical composition at the conservatory in Cologne and wanted to use some of the techniques of contemporary classical composition for the improvisation projects he staged with his smaller ensembles or with the larger Globe Unity Orchestra.

其他的音乐家如萨克斯手Peter Brötzmann或贝司手Peter Kowald发展出了一种非常具有表现力的自由即兴风格,通常在声音和手法上生猛极端,且包含了一种反叛者姿态的政治隐喻,他们反抗当时德国社会的无能,因其尚未有正视其黑暗的政治历史的决心和勇气。

Other musicians such as the saxophonist Peter Brötzmann or the bassist Peter Kowald developed a very expressive idiom of free improvisation, often brutally excessive in sound and approach, often also having political undertones of a revolt against a society which still had not quite found its resolve with its dark political past.

那些年间,爵士乐中诞生出与众不同的欧洲之声,甚至在不同国家之间都大相径庭。一个挪威的爵士乐手演奏的音乐听起来就不同于法国、意大利、英国、荷兰或德国乐手的演奏。

Jazz developed distinctive European sounds during these years, and more so, it developed distinctive national sounds even, through which the music played by Norwegian jazz musicians would sound different from that played by French, Italian, British, Dutch or German musicians.

西欧和美国的爵士乐存在的一个机制性而非音乐性上的主要区别是: 西欧有(公共基金)资助艺术的传统。爵士乐在欧洲很快被作为是一种当代艺术形式,甚至不止于此,它是一种可以表达欧洲人灵魂的艺术形式,就如同爵士乐可以最大程度地表现美国人,尤其是美国黑人的灵魂。在上世纪60年代早期,歌德学院就开始遣派爵士乐手代表德国的艺术音乐到世界各地演出。音乐会和音乐节的举办资金来自于纳税人。公共广播电台不仅会纪录爵士现场,还会参与制作,让音乐家有机会实验和发展新的创作。同一家公共广播电台甚至拥有属于自己的薪酬不菲的电台大乐团,这些乐团至今依然位居世界上最好的大乐团之列。

There was one major difference between Western European and US American jazz, and that was organizational more than musical: In Western Europe you had a tradition of funding the arts. Jazz soon was considered a contemporary art form, and more even, an art form that could express the Western European soul just as much as it expressed the American, the African-American soul. The Goethe-Institut had started to send jazz musicians around the world in the early 1960s to represent German art music. Concerts, festivals were sponsored through tax payers' money. The public radio stations not only recorded jazz concerts but even produced them, and thus gave musicians the chance to experiment and to develop new projects. The same public radio stations even had their own, well-paid radio big bands which to this day belong among the best jazz orchestras in the world.

如你们所见,我们从过去讲到现在了。这段德国爵士乐历史的简短回顾就到此为止,接下来我将介绍达姆施塔特爵士研究所,然后再与大家分享相关的音乐。

As you can see, we are coming into the present time, and to wrap up this short history of jazz in Germany I will get back to the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt – only to return to the music in a short while again.

达姆施塔特爵士研究所的成立,缘起于一个名叫Joachim Ernst Berendt的知名乐评人、记者、作者兼爵士乐制作人。他把他的唱片、书籍、报刊、照片等个人收藏全部卖给了达姆施塔特市政府,纳入其主要的二十世纪音乐文献收藏。达姆施塔特位于法兰克福以南,驱车一个半小时。达姆施塔特市不大,只有15万居民,却足以让人自豪。直到1944年,这里还是区政府所在地。但是二战期间,它被英国皇家空军的炮弹夷为平地。然而,这里的人民一直渴望着达姆施塔特成为政府所在地,希望这个城市变得特别,成为世界的中心。这或许能解释为什么很多文化机构都安居于此,这些机构基本上都依存于居住在这个城市的纳税人资助。

The Jazzinstitut Darmstadt was founded after Joachim Ernst Berendt, a major critic, journalist, author and producer of jazz had sold his collection of recordings, books, periodicals, photos etc. to the city of Darmstadt to be included in their major collection of 20th century music documents. Darmstadt, about half an hour south of Frankfurt, is a city of 150,000 inhabitants, not big, however very proud. It was the seat of the regional government until 1944 when, during the Second World War, the city burned to the ground completely after having been bombed by the Royal Air Force. The attitude of being a government seat, however, of being special, of being the center of the world, never left the people in Darmstadt which may explain the many cultural institutions at home there, all basically financed by the tax payers living in the city.

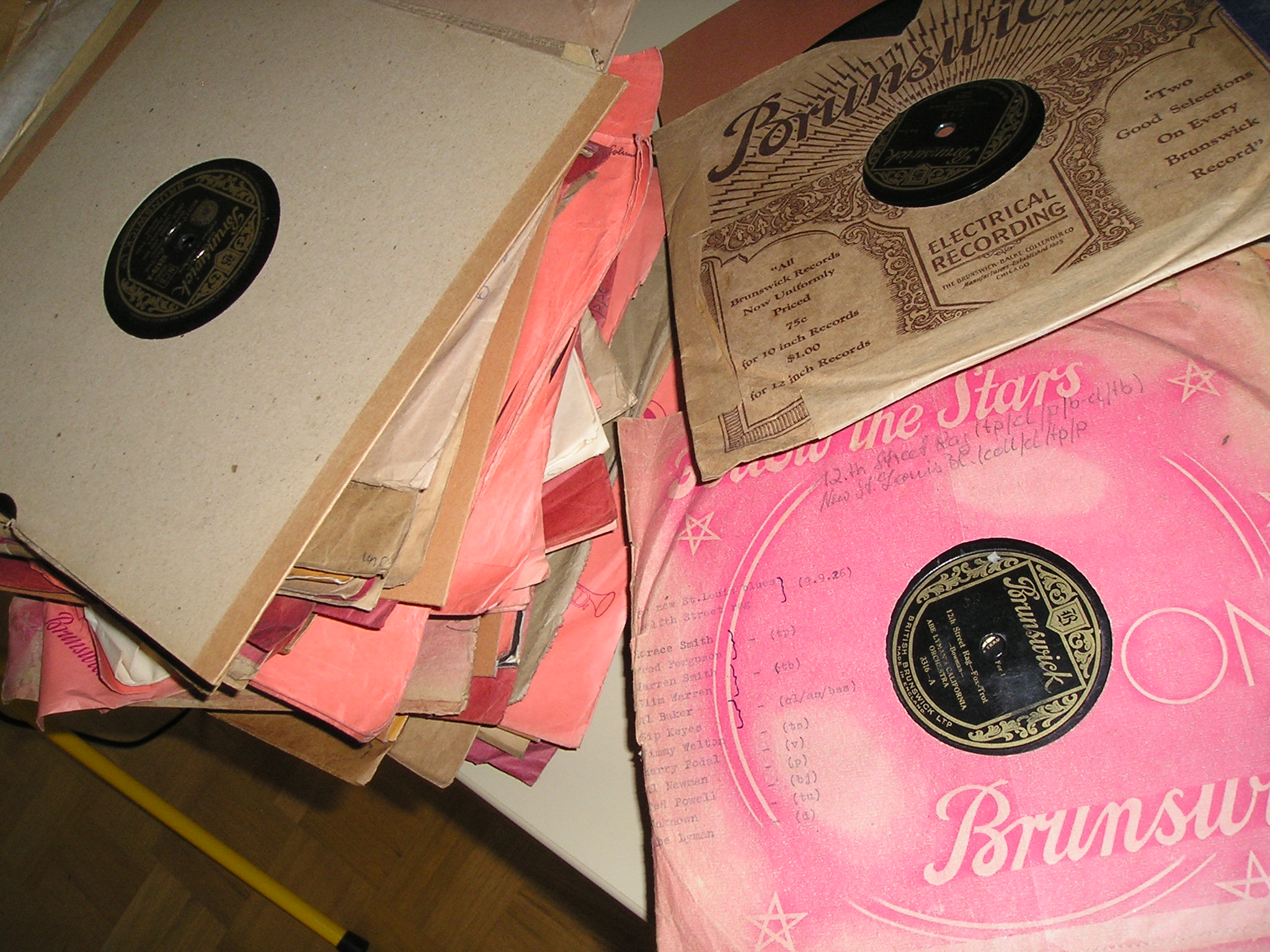

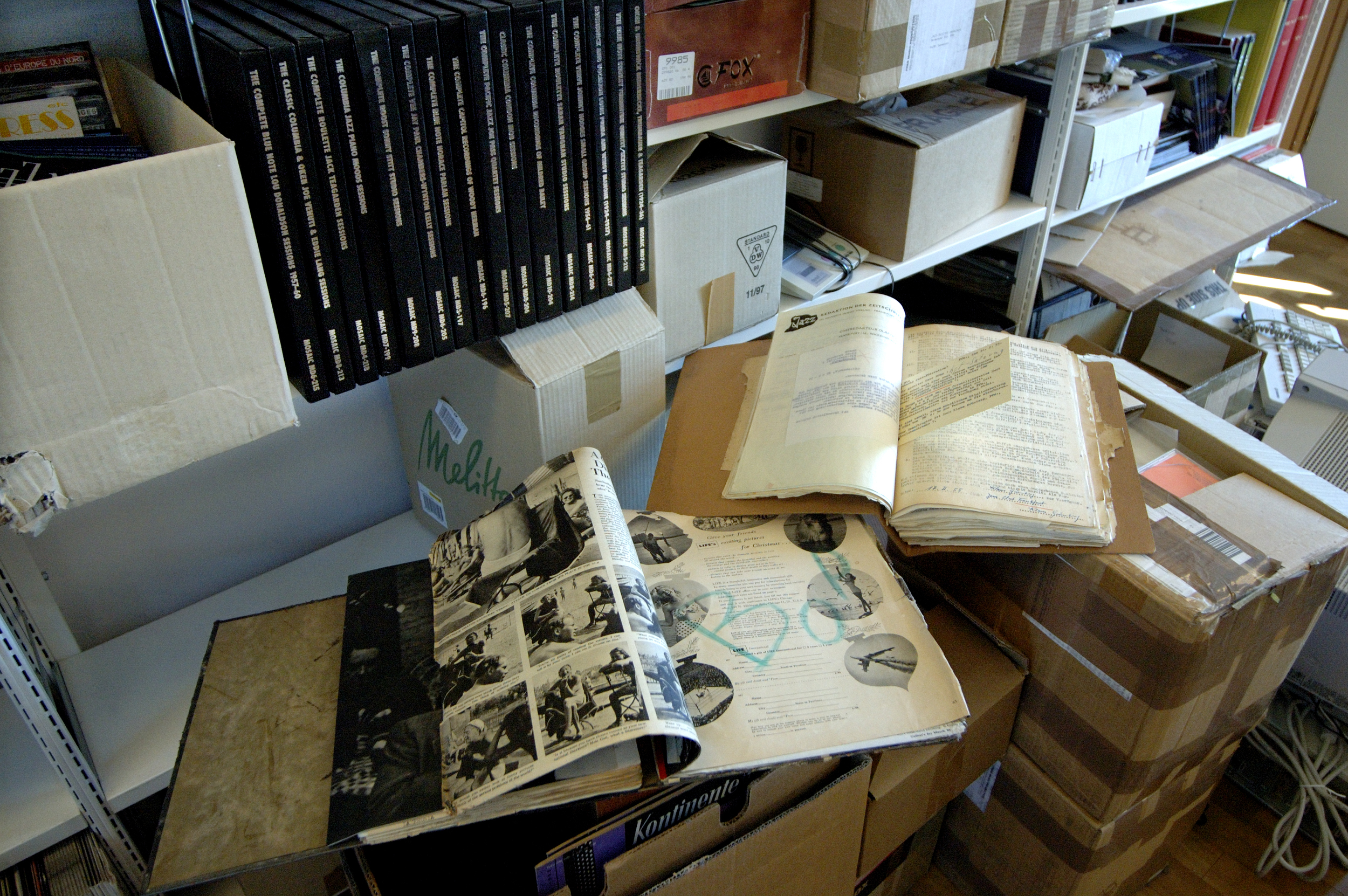

爵士乐研究所成立于1990年,拥有黑胶、78转唱片、CD、视频等各类格式的庞大收藏约8万个音像品。我们有美洲大陆外最多的爵士乐书籍和期刊收藏。我们还有大约5万张照片和上千张海报。我们是一个档案馆,也就是说我们要收集从诞生之初到最近发展的整个爵士乐历史。世界上还有其他的爵士资料馆,最重要的两所都在美国。一所是位于新泽西州纽瓦克市的爵士乐研究中心,它拥有更加丰富的藏品,包括一些过世乐手的遗物。在那里你可以见到Fats Waller或Mary Lou Williams的手稿。以及从爵士诞生初到上世纪六七十年代的一些乐手的个人手迹。另一所是位于新奥尔良市的霍根资料馆,它的档案记载了路易斯安那州的爵士起源和音乐环境。

The Jazzinstitut was founded in 1990. It holds a huge collection of approximately 80,000 recordings of all formats: vinyl LPs, 78 RPM records, CDs, videos. We have the largest book and periodical collection about jazz on our side of the Atlantic. We have about 50,000 photos as well as thousands of posters. We are an archive which means we try to collect the complete history of jazz from its beginnings up to the most current developments. There are other archives on jazz around the world, the most important two in the United States: The Institute of Jazz Studies in Newark, New Jersey, has a much larger collection and holds many estates of diseased jazz musicians. There you will find the music manuscripts of Fats Waller or Mary Lou Williams as well as the personal papers of many musicians from the beginnings of jazz up into the 1960s and 1970s. And the Hogan Archive in New Orleans documents the origin of jazz and its musical environment in the state of Louisiana.

那么,达姆施塔特爵士研究所与这两所资料馆以及其他一些欧洲类似的资料馆有什么区别呢?首先,我们不仅仅是一个资料馆。我们认为要了解历史,就必须要了解现在,并且关心未来。因此我们做的并不仅是一种让历史存活的保护活动,还会去支持艺术家继续不断地努力发扬这种艺术形式,不论它将去向何方。

What, then, makes the Jazzinstitut in Darmstadt different from these other two or from similar European archives? For one, we are more than just an archive. Our understanding is that to understand jazz history you must know about its present and you must care about its future. And by that I do not just mean preservational activities about keeping the history alive, but I mean to support artists in their efforts to continue to develop the art form, no matter where it might lead.

其次,我们是一个档案性质的机构,但在我们城市的大部分纳税人眼中,我们更多时候是演出的组织者,我们的场地就在研究所地下的演出空间。是的,我们自己有一个大约能容纳100人的俱乐部,有非常棒的斯坦威大三角钢琴和极好的原音乐器。1997年,我们非常幸运地邀请到德国最重要的萨克斯手之一Heinz Sauer为我们的现场作开幕表演,那之后他也在研究所多次演出。我们每周五举办一场音乐演出,当我在这里说“我们”,其实不只是我们爵士研究所的区区三个馆员,还有本地自发的爵士力量,包括乐手、乐迷和狂热爱好者,他们会在我们的俱乐部做自己的系列演出,负责饮食服务,在吧台买卖饮料等等。

We are an archive, then, however many of the taxpayers in our city mostly know us as the organizers of concerts in our own concert space underneath the Jazzinstitut. Yes, we have our own club holding approximately 100 people, with a wonderful Steinway piano and excellent acoustics. We were lucky to have one of the most important German saxophonists to open the performance space in 1997: Heinz Sauer who since then has played at the Jazzinstitut a number of times. We organize about one concert a week, every Friday, and if I say “we”, that is not only us, the relatively small staff of three at the Jazzinstitut, but a local jazz initiative of musicians, fans and enthusiasts, as well, who will put on their own concert series and who are responsible for the catering at our club, buying and selling the drinks behind the bar.

我们最主要的一个系列音乐会名为“爵士对话”(JazzTalk)。我们邀请了很多乐手和乐队做常规的演出。但是在中场休息时,我会在舞台上坐下来和乐手们对谈,谈谈他们的艺术和影响,谈谈他们如何发展自己的个人风格,或者就谈谈他们前半场的演出。这并非意图要成为一堂给观众上的课,更在于为他们提供一个了解音乐家和他们的美学方式的机会。很多观众告诉我们在“爵士对话”的音乐会中,他们发现自己听后半场时和前半场的感受很不一样,正是因为中间安排了这个关于音乐的对话环节。

Our main concert series is one which we call “JazzTalk”. For it we invite musicians and bands to play a regular concert. However, after the intermission I will sit down on stage with the musicians to talk about their art, about influences, about how they developed their personal style or simply about the first set. This is not so much meant to be a lecture for the audience than to give them the opportunity to get to know the musicians and their aesthetic approach. Many audience members tell us that at JazzTalk concerts they will hear the second set differently from the first, simply because of the conversation we had about the music in between.

达姆施塔特的爵士乐迷们还知道我们从1992年起每年都会举办一次工作坊。每年我们会邀请德国乃至世界上那些最出色的音乐家来为60名学员上一整周的课。这些学员不一定非得是专业乐手或立志成为音乐家的人,但他们想要在乐器演奏方面学到更多东西,尤其是即兴艺术。我想说,工作坊并不需要培养下一个Miles Davis,但是它绝对能让达姆施塔特市拥有你所能想到的最好的观众:他们懂得舞台演奏,从切身的实践中理解即兴的意义;他们从不满足于普通的标准曲,而是乐于接受挑战,渴望听到新的东西。

Darmstadt jazz fans also know us for an annual workshop which we organize since 1992 and in which we invite the best musicians from Germany but also from other countries to teach about 60 students each year for a whole weak. These students are not necessarily professional musicians or strive to become musicians; however, they want to learn more about their instrument and especially about the art of improvisation. These workshops, as I like to say, will not necessarily produce the next Miles Davis, but they will make sure that Darmstadt has one of the best audiences you can imagine: people who know about being on stage, who know from first-hand experience what it means to improvise, who will not be content with normal standards but who like to be challenged, to hear something new.

每隔一年我们都会举办一个名为达姆施塔特爵士论坛(Darmstadt Jazzforum)的国际研讨会。会议总是围绕一个特定的主题展开,我们会邀请一些音乐学家、社会学家、文学批评家和其他领域的学者,记者和乐手也会对主题发表自己的看法。往期爵士论坛的主题有“爵士在德国”、“爵士在欧洲”、“爵士和语言”、“爵士和流行音乐”,有如Duke Ellington和Albert Mangelsdorff这样音乐家的主题,也有关于爵士乐教育和爵士乐评论等方面的主题。我们上期的爵士论坛主题叫“爵士辩论(Jazz Debates)”,讨论了历史上和当前爵士的论述中不同的辩论,以及所有这些辩论如何影响今天我们对这种音乐的认知。明年举办第14届达姆施塔特爵士论坛,聚焦性别的主题,同时也将迎来爵士研究所创建25周年。我们将要探讨女性在爵士乐中的重要意义,话题包括男性气质之于爵士即兴以及同性恋乐手在爵士中的影响等等。除此之外,我们还会探讨关于个人背景对于音乐创作的重要性,以及“你是谁”如何导引“你演奏什么”。

Every other year we put on an international conference, called the Darmstadt Jazzforum. It always centers around a specific topic, and we invite musicologists, sociologists, literary critics and other scholars, but also journalists and musicians to give us their input on the topic. Past Jazzforums focused on “Jazz in Germany”, “Jazz in Europe”, “Jazz and Language”, “Jazz and Pop Music”, on musicians such as Duke Ellington or Albert Mangelsdorff, on jazz education, on jazz criticism and so on and so forth. Our last Jazzforum was called “Jazz Debates” and discussed the different debates in jazz history as well as present jazz discourses and how all of them influence our current understanding of the music. Next year we will celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Jazzinstitut with the 14th Darmstadt Jazzforum focusing on a gender topic. We will discuss the importance of women in jazz, subjects like masculinity in jazz improvisation, but also the input of gay or lesbian musicians in jazz history. More, though, we will talk about how important your personal background is for the music you are making, about how who you are informs what you play.

每一届爵士论坛都会完整地存档于我们的“爵士探索之达姆施塔特研究”(“Darmstadt Studies in Jazz Research”)书系中,这也是德语爵士资料的一个重要来源。此外,爵士研究所还会印刷一些记录我们策划过的展览的小册子,这些展览包括了在我们自己小画廊的展览以及为各种音乐节或其他活动所办的巡展。我个人也撰写过一些以爵士为题材的书籍,比如一本深入研究Modern Jazz Quartet的音乐的书,以及两本关于Louis Armstrong和Charlie Parker的人物传记,还有更多的作品正在筹备当中。之前我提过我们只有三名馆员,但我们在这样一个规模下获得了世界范围的广泛赞誉,我为此感到非常自豪。甚至来自爵士乐发源地——美国的学生,也被老师要求在论文写作前,首先咨询我们以了解他们所需的学科著作。

Each Jazzforum is thoroughly documented in our book series called “Darmstadt Studies in Jazz Research”, a major German-language source of information on jazz. Apart from that the Jazzinstitut has published small brochures and booklets documenting some of the exhibitions we have curated both at our own small gallery and as traveling exhibitions to be rented from us for festivals or other events. I have personally written several books on jazz subjects, such as a detailed study on the music of the Modern Jazz Quartet or two biographies about Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker, and I am working at more to come. I told you shortly that we have a staff of only three. I am proud to say that for such a size we have a pretty good and worldwide reputation. Even students from the United States, the birthplace of jazz, are required to first contact us about any literature on their preferred subjects before starting their work on a paper or thesis.

我们所做的事情已经不少了,不是吗?然而所有的这些,包括整理归档,组织音乐会、音乐节,举办工作坊和展览,进行开创性的爵士研究,都只不过是我们日常工作的一部分。近些年我们工作的一个主要方面变成了,我愿意称之为“爵士游说”。为此,我们必须回到音乐的世界,回到二十一世纪的德国爵士场景。

It is quite a lot that we do, no? Yet, even all of this, archiving, organizing concerts, festivals, workshops, exhibitions, and doing groundbreaking work in jazz research, is only part of our daily work. A major aspect of our work in recent years has become what I would call lobbying for jazz. And for this we must come back into the music world, the German jazz scene of the 21st century.

你可能会注意到,在1949年至1989年间,德国爵士有两个截然不同的场景:西德的爵士乐一派活跃景象,乐手可以近距离地与他们的美国同行交流。这个场景生机勃勃,你可以在各种俱乐部和音乐节上看到来自世界各地的爵士巨星和冉冉升起的新锐。另一方面,东德则发展出了自成一派的爵士风格,在很多方面和西德不尽相同。在那里,音乐家在他们的作品里更多地反射出自己的处境。在一个社会主义国家里,他们很难接近西方音乐,也没有什么机会接触美国乐手。在上世纪60年代,结合德国民俗传统及国家的社会主义背景,如Hanns Eisler等东德的作曲家和爵士乐手发展出了一套与众不同、清晰可辨的音乐语汇。几乎同西德在同一时期,东德的爵士音乐家们也走向了自由即兴。不过,东德的音乐风格更多一丝幽默感,并且在形式上的轮廓更加清晰。

Germany, as you may be aware, had had two jazz scenes between 1949 and 1989: There was a very active scene in West Germany, where musicians could stay in close contact with their American colleagues. It was a lively scene, with many clubs and festivals at which you could hear the big stars of jazz as well as up-and-coming musicians from all around the world. East Germany, on the other hand, had developed its own kind of jazz, in many ways different from that in the west. There, musicians reflected upon their own surroundings in a socialist country, without such easy access to Western music or the possibilities of close contact with American musicians. By the 1960s, East German jazz musicians had developed a clearly recognizable musical idiom that made use of German folklore traditions as well as referred to the socialist background of their own country, composers such as Hanns Eisler and others. Just as in the West, the East German jazz musicians had arrived at a level of free improvisation; however, the Eastern style had a little bit more of humor in it, and it was a little clearer in its formal outline.

1989年两德统一。我跟你们说过,爵士研究所是在1990年成立的,也即是这政局变动的仅一年之后。因此,各种各样的问题就迎面而来,那些音乐家所面临的问题也同样落到了我们的头上。统一,就意味着公共资金的用途会突然有很大的转变。德国终究必须合二为一,两套相异的基础设施必须合并,原来东西德边界两侧的道路必须提到同等水平,经济和政府系统也是如此。在此新形势下,政府不会优先考虑艺术支持,大众也不会首先想要去音乐会现场。因此,1989年德国的统一在政治上是极好的改变,但它同时也导致了公众对艺术的接纳度急转直下,尤其是基于公共津贴的艺术形式。

Then came 1989 and the reunification of the two German states. Now, I had told you that the Jazzinstitut was founded in 1990, only one year after those political changes, and we were soon faced with major problems which the musicians had and approached us with. Reunification meant that a lot of public finances suddenly had to be used differently. Germany, after all, had to make one state out of two. It had to combine two divergent infrastructures; it had to bring roads to an equal level on both sides of the former inner-German border, as well as economic and government systems. The funding of the arts was neither a first priority for the government nor was going to concerts the first priority for many of the people under this new situation. As wonderful as the political changes from 1989 thus were for Germany as a nation, they also brought about a change in the artistic acceptance especially of art forms which depended on public subsidies.

因此,爵士研究所成立后最先收到的来自音乐方面的诉求,都是求助的呼喊。音乐家意识到爵士研究所或许并不仅仅是个保存历史的资料馆,而我们也意识到,作为一个公共组织,我们担负着帮助改善当前音乐环境的使命。我们便开始询问这些音乐家:除了钱,你们真正需要的是什么?我们要用什么方式来促进爵士乐坛的发展?我们得到的最多的答案是:我们需要一个“演出指南”,我们需要一个爵士酒吧、音乐节、厂牌及所有活跃在当今的其他专业乐手的清单。由于无可参考,我们便开始自己收集信息,不久出版了第一本我们称之为“爵士探路者”的书籍,它的最新版有超过400页关于德国爵士乐环境的信息。它不只是一个爵士场地的清单,还包含了很多俱乐部和舞台的详细资料,比如钢琴、音响系统、联系人等等。它也包含了德国津贴系统的信息,如果你需要申请公共基金资助,你可以在上面找到应该寻求谁的帮助。我们列出了德国16个联邦政府分别支出多少津贴在爵士乐上,也会确保每一版新书都送到参与支持艺术的政客和政府机构手上。总之,我们渐渐地产生了政治意识,并努力做到了让我们的声音在地区和国家标准上都被听到。

The first calls we received from the music scene after the founding of the Jazzinstitut, thus, were shouts for help. Musicians realized that the Jazzinstitut might be more than just an archive preserving history. And we at the Jazzinstitut realized that as a public organization we might be in a position to help the current music scene. We started to ask the musicians: What is it that you really need, apart from money? In what way could we help to strengthen the jazz scene? And the answer we received most often was: We need a “gig guide”, we need a listing of jazz clubs, festivals, record labels and all of the other professional players on the scene. As there was nothing of the sort, we started collecting information and soon published the first of our, as we called it, “Pathfinder to Jazz” which in its last edition comprised more than 400 pages of information about the German jazz scene. This was not just a listing of venues but included detailed information about the many clubs and stages, about pianos, sound systems, the people to contact and so on and so forth. It also included information about the subsidy system in Germany, about whom to turn to if you need public funding. We listed how much money each of the 16 federal states was spending in regard to jazz funding, and we made sure to send each new edition of the book to all of the politicians and federal agencies involved in supporting the arts. In short, we developed a political consciousness, and we managed to get heard on both a regional and a national level.

爵士研究所帮助搭建了一套支持爵士乐的国民构架,这个来自爵士乐各个领域同行的圈子包括:音乐家、音乐会承办者、记者、唱片公司代表、教育者等等,还有更多。通过这个被称之为“爵士联盟会议”(“Federal Conference on Jazz”)的组织,我们完成了德国爵士大会(German Jazz Meeting)的创建。它是一个展会节日,现在由不莱梅的集贸公司接管,现今德国的爵士项目都会再次展示给受邀的来自世界各地的记者和音乐会承办者。爵士乐,终究是一种需要在现场聆听的音乐,我们也确信这些承办者们需要听到乐手的现场,才能知道当今乐坛正在发生什么,而不仅是通过唱片。我们还通过这个组织说服联邦政府设立了一个俱乐部奖项,每年表彰那些在爵士、摇滚和流行乐领域有自己杰出的文化项目的俱乐部。

The Jazzinstitut was instrumental in establishing a national structure for jazz support, a circle of colleagues from all the fields of jazz: musicians, concert promoters, journalists, label representatives, educators and much more. With this organization, called the “Federal Conference on Jazz”, we managed to establish the German Jazz Meeting, a festival which now has been taken over by the Trade Fair Company in Bremen, in which current jazz projects from Germany are presented to invited journalists and concert promoters from all around the world. Jazz, after all, is a music to be heard in live concert, and we are convinced that promoters need to hear the musicians in action, and not just on record, in order to know what is happening on the current scene. With this organization we also managed to convince the federal government to establish what is called a club award, which annually honors clubs from the field of jazz, rock and pop for their advanced cultural programs.

现在我们来听一段Hyperactive Kid乐队去年演出的录音……

Listen to a clip of the band Hyperactive Kid from last year...

这是一个时刻变化的世界,我们都需要随机应变。古典音乐的世界长久以来都有支撑它们的体系,流行音乐则是被商业性的音乐工业所操控,而爵士乐一直依靠的是乐手自己和志愿者们。爵士乐的背后几乎从来没有专业的体系构架。老一辈的乐手和乐迷说,连组织演出时的自发性,也属于爵士乐的本质。但年轻的乐手不以为然,他们成长在爵士乐被当作主流艺术形式之一的世界里,他们为自己的演出要求专业的场地和匹配的报酬。他们要求一个财务的体系来确保他们工作。他们首先把自己视作艺术家。然而,作为即兴音乐家他们的工作也许可以被认为是,如我所述的,当代音乐的“研究实验室(research laboratory)”。就像任何一种研究一样,这样一个实验室里的研究试验需要资金的支持,并且没人能够理所当然地期待它们全部获得成功。当我们持续改善文化环境时,我们需要支持这种研究,而作为一个公共机构,我们研究所的职责就是让政客们了解,艺术并不单是关于美感和娱乐,它还是一场持续的对话,是一个关于世界正在发生活动的论述。艺术是人类决策的一面镜子,也可以是一个社会的意识体现。对于正在发生的事情,它们永远是有批判性的。它们会随行,会支持,会阻碍,会震荡。艺术需要自由。而这种理想的自由只有在它们所成长的体制的资助下才会高飞。

It is a changing world, and we all need to adjust to the changes. Whereas the classical music world since long had their support structures, whereas the popular music scene is being handled by the commercial music industry, jazz always depended on the musicians themselves, on many volunteers. The jazz scene hardly ever had a professional structure behind it. There are both musicians and fans from an older generation who say that this improvisational nature even of organizing concerts is at the core of the music. However, younger musicians think differently. They grew up in a world in which jazz has been recognized as a major art form, and they demand both professional venues and adequate payment for their concerts. They demand a financial structure which allows them to do their work. They see themselves as artists first. However what they do as improvising musicians might be considered, as I like to phrase it, the “research laboratory” of contemporary music. Like in any kind of research, experiments in such laboratories need financial backing and one cannot necessarily expect them to all be successful. Yet, as we continue to develop as cultural environments, we need to support this kind of research, and our (the Jazzinstitut's) duty as a public institution is to make politicians understand that art is not only about beauty and entertainment, but that art is a continuing dialogue, a discourse about what is going on in the world. The arts are a mirror of human decisions. They can be the consciousness of a society. They will always be critical of what is going on. They will accompany, they will support, they will disturb, they will shock. They need to be free. And this freedom ideally needs to be financed by the system in which they grow.

所以,2014年,我们相聚在这里。让我回到德国爵士,回到此次讲座的剩余部分吧。

So, here we are, in the year 2014. Let me get back to German jazz for the remainder of my presentation.

现今的德国爵士乐的状况因地而异。在德国的每一个大城市都有爵士酒吧和音乐节。近些年,柏林是爵士的活动中心,科隆紧随其后。汉堡、慕尼黑、斯图加特都显露出勃勃生机,即使一些较小的城市也发展不错。德国大多数的音乐学院都设有爵士课程,学习爵士乐的学生太多了,以致于我们有时都会疑惑他们要上哪去找观众。不过学习爵士乐并不只是要成为一个好的爵士乐手,你也能做一个好的音乐老师或录音伴奏乐手。演奏爵士乐的能力被视为一个乐手教育的基础部分。

The German scene today is quite varied. You will find clubs and festivals in every major city in Germany. Berlin is the center of activity these days with Cologne not far behind. Hamburg, Munich and Stuttgart have a lively scene, and even some of the smaller cities. We have jazz programs at most of the German music universities, and the students who study jazz are so many that we sometimes ask where they will find their audience. However you study jazz not only to become a good jazz musician, but also to become a good music teacher or a good studio musician. To be able to play jazz is seen as an essential part of a musician's education.

柏林,作为德国的首都,虽然位于中心,但房租和生活成本相比其他城市仍然便宜。你会发现城里很多不同领域的艺术家会激发你的创造力,或能让你实现任何你能想到的计划。很多欧洲其它国家以及美国的乐手移居柏林,他们享受这个城市充满创造力的精神。我们都知道类似的艺术中心在逐渐式微,但我坚信未来柏林仍会是一个艺术的热点坐标。

Berlin, though is at the center. The German capital still has relatively cheap rent and living costs are lower than in other cities. You will find many artists from all different fields in town to stimulate your creativity or to enable you to realize whatever project comes to your mind. Many musicians from other European countries moved to Berlin, but also musicians from the USA. They enjoy the creative spirit of the city. We all know that such artistic centers move with the flow, however I am sure Berlin will remain a hotspot for years to come.

你也许会问,德国的爵士乐与其它欧洲国家的爵士乐究竟有何不同?它与美国爵士乐又区别何在?互联网的出现正在使这个世界变得越来越小,地方性的音乐风格融入一般性的全球音乐语言,每一个音乐人都可能被甚至从未谋面过的其他每一个音乐人所影响,难道不是这样吗?

What makes German jazz different from jazz in other European countries, you may ask. And how does it differ from American jazz? Has not the world with the advent of the internet become so small that local musical idioms dissolve into a general global language in which each and every musician is able to be influenced by each and every other, even if they have never met?

我的答案是:是,也不是。是的原因在于,爵士已经带着这种音乐的基本词汇和语法传遍世界:爵士乐特殊的即兴手法,经由乐手间的协作而发展出一种音乐结果的特点,似乎已成为一种普遍的方式。世界上大部分爵士乐手肯定都会类似地受到一些美国爵士标准范式的影响,都会演奏一些相同的标准曲目,也都懂得布鲁斯的含义(就算不懂得布鲁斯的感觉)。

My answer would be: Yes and no. Yes, jazz has spread all over the world, and with it the basic vocabulary and the basic grammatical rules of this music: Jazz's specific way of improvising, of collectively developing a musical result seems to have become a universal approach. Most jazz musicians all over the world have definitively had a similar background in being influenced through some American role models, in having played some of the same standard compositions, in knowing the meaning (if not the feeling) of the blues.

这种源于美国黑人的音乐已经被广泛接受,然而真正自我的爵士演奏则一直在探寻着更多。爵士乐里的真正常规是不假思索。如果你问一个爵士老炮怎样才能成为一个好的爵士乐手,他们可能会说:“哥们,玩你自己的!”他们的意思是你必须发展出一套你个人的音乐风格,而不只是重复他人的表演。是的,吸收那些大师的音乐,向他们学习。但是假以时日,你需要深入你自己的音乐背景,试着发现你的声音以及有什么私货拿得出手。

The African American origin of the music is universally accepted, and yet, jazz always asked for something else if it were to be played authentically. The most universal rule of jazz is one people often don't think about. If you ask older jazz musicians what makes a musician a good jazz musician, they might answer: “Play yourself, man!” By which they mean that you will have to develop your own personal approach to the music and not just repeat what others play. Yes, absorb the music of the great masters, learn from them, but at one point you need to look into your own musical background, and try to find out how you sound and what you personally have to bring to the table.

个人主义法则使爵士乐在不喜欢异己分子的极权国家举步维艰,但也正因如此而使得德国、法国、南美或中国演奏的爵士乐与美国有所区别。我之前就讲到,在德国分裂时期,即使东德和西德的爵士乐也听起来各不相同。更确切地说,这种不同的背景、不同的方式和音乐的关联是很重要的。如果德国的音乐家只是想让音乐听起来像美国的音乐家那样,那么他们的音乐就永远不会是不可复制的。但是,如果他们“玩他们自己的”,他们听起来就会和美国音乐家不同。

This rule of individuality was what made jazz a difficult subject in totalitarian countries which never liked nonconformity, but it also is what makes jazz played in Germany or France or South Africa or China different from jazz as being played in the United States. I told you before how even the music in the two German states sounded different for the time of their forced separation. And, let me make this clear, this difference of approach, this difference of background is important for the relevance of the music. If German musicians would just try to sound like American musicians their music would never be authentic. If they “play themselves” however, they will sound different from their American colleagues.

这样的事例曾经发生,并依然在发生着:美国乐手来到欧洲,被欧洲乐手演奏的音乐激怒——因为欧洲爵士更少植根于布鲁斯音乐,因为欧洲爵士打破了传统,或者干脆说,它引进了不同的传统作为参照点。有时候,欧洲的爵士即兴可能听起来根本不像爵士,却更接近于当代乐曲领域的音乐实验。但正如我想对那些持怀疑态度的美国人解释的,这就是美国爵士乐赠予世界的礼物:一种需要适应所到之处文化的音乐,一种需要个人参与,需要改变传统才能使其获得荣光的音乐。这也是迄今为止,爵士乐于我来说具有高度的道德、伦理及政治价值的原因之一:这是一个可以超越政治、宗教和文化差异进行沟通对话的典范。歌德学院自上世纪60年代以来把爵士乐奉为代表德国的一种艺术形式,是有其道理的。爵士乐手在巡演时,能够立刻找到与来自其它文化的音乐家沟通的方法,不论对方是爵士同道还是民谣或古典乐手。爵士乐手习惯于调整自己的艺术形态来进入其他乐手的演奏,并将其一并纳入到整个的艺术处理中。爵士近些年来正在成为一种现代管理的模本,它也可以是一种外交手段或是克服跨文化差异的典范。

It happened and it still happens that American musicians come to Europe and are irritated by what European musicians are playing, because it is less rooted in the blues, because it breaks with traditions, or rather it introduces different traditions as points of reference. Sometimes, European jazz improvisation may sound not like jazz at all but much closer to the experiments in the contemporary composed music field. But that is, as I try to explain to skeptical Americans, America's gift to the world: a music which requires to be accommodated to the cultures it travels to, which requires personal involvement, which requires the traditions to be changed in order to be honored. That is also one of the reasons why jazz for me to this day has a highly moral, ethical and political value: It is a model for communication transcending political, religious or cultural differences. There is a reason why the Goethe-Institut embraced jazz as an art form to represent Germany from the 1960s onward. Jazz musicians traveled and at once found a way to communicate with musicians from other cultures, whether they were fellow jazz musicians or folk musicians or classical musicians. The jazz players are used to accommodate their art form, to take up whatever others are playing and incorporate it into the artistic process. Jazz has in recent years become a model for modern management; it could just as well be a model for diplomatic communication or for overcoming cultural differences.

从我播放影片之前的演讲,你们能感觉到我是一个乐观主义者吧。爵士乐对我来讲并不是这个世界上最棒的东西。它只是承认差别。它述说包容。爵士乐手会让你演奏自己的音乐,然后他们的演奏汇入你的个人风格,而不是强迫你以“他们的”方式演奏。他们知道,声音的差异才是声音最有意思的地方。毕竟,爵士乐是且一直都是一种“惊喜之声”。无论何时去现场,在美国或德国,或是像此刻在中国,我都在寻找那些真正的惊喜。无论何时我都会因惊喜而开心,因为我知道这个世界仍充满生气,并流转变化……

From what I have said before this clip, you can see, that I am quite an optimist. Jazz to me is not the best of all worlds. It just acknowledges difference. It speaks of tolerance. Jazz musicians will let you play what you play and try to incorporate your personal style instead of forcing you to play “their” way. They know that only the sound of difference will be the sound of interest. Jazz is and remains, after all, the “sound of surprise”. Whenever I go to a concert, be it in the United States or in Germany or here in China, I am on the lookout for exactly those surprises. And whenever I am surprised I am happy because I know the world is still alive and turning…

非常感谢

Fēichánggǎnxiè (Dankeschön)

文本信息 Text Information

来源 Source:Wolfram Knauer提供英文讲稿 English script provided by Wolfram Knauer

翻译 Translating:Subi,Liamaerd,尹思卜 Midori Yin

校对 Proofreading:陈鹿鹿 Nostalgia Chan